Part 2: First Impressions – From Changi to Pasir Ris to Orchard Road

Arrival at Jewel Changi Airport

|

| Jewel Changi Airport |

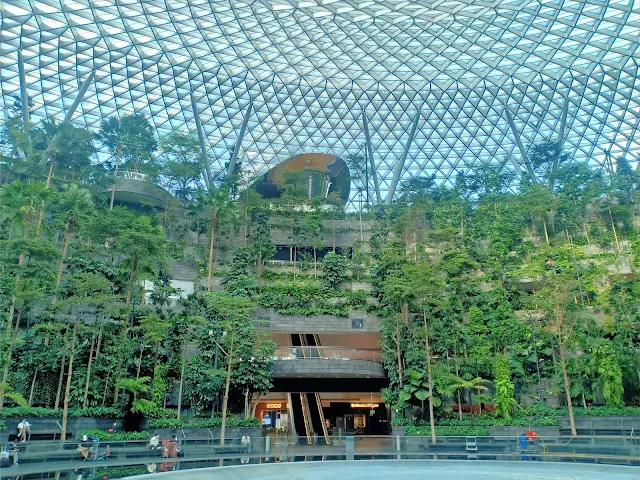

Stepping into Jewel Changi Airport felt like stepping into a different world. The centerpiece of the complex, the Rain Vortex—the world’s tallest indoor waterfall—was surrounded by lush greenery, open atriums, and skylit interiors. The architectural design by Safdie Architects blends functionality with aesthetic experience, transforming an airport into a leisure destination. Everything was intentional: the flow of people, the signage, the rest areas, and the seamless integration of nature into built form.

Even as I admired the scale and complexity of Jewel, I noted how calm and quiet it was despite the number of people. There were families taking photos, business travelers calmly navigating, and airport staff moving efficiently. It reminded me that architecture can manage chaos, not by restricting people, but by guiding them intuitively.

|

| Street View of The Beat. Sports Hotel |

Our group headed to the MRT station for the ride to our accommodation, The Beat. Sports Hotel. It was my first chance to observe the city from the ground level. What stood out immediately was the cleanliness of the streets and the presence of greenery everywhere—tree-lined avenues, manicured boulevards, and potted plants even at road dividers.

Old trees were not just preserved but celebrated. Many had custom-designed metal grates and irrigation systems that ensured their health. Street furniture, such as benches and bicycle racks, were evenly spaced and well-maintained. We even came across a group of workers cutting canvas sheets on the pavement—a sign of multifunctional public spaces that support community use, not just vehicle flow.

Exploring Pasir Ris HDB Township

|

| View from Pasir Ris MRT station |

Our main observation for the day was focused on Pasir Ris, a residential town in eastern Singapore. Designed as a self-sufficient neighbourhood, it embodies the principles of sustainable planning: accessibility, integration of green space, and a community-first layout.

Each HDB (Housing Development Board) block was nestled

within a cluster of facilities including community gardens, children’s

playgrounds, exercise zones, and wide pedestrian walkways. What impressed me

the most was Pasir Ris Town Park—an expansive public park featuring a large

saltwater fishing pond, food stalls, bridges, jogging trails, and shaded

gazebos. This wasn’t just a park for occasional use; it was clearly an

essential part of residents’ daily lives.

|

| 15-Minute concept of urban fabric (Paris En Commun,2020; Yıldırım and Özmertyurt,2021) |

I saw families enjoying time together, elderly people

walking or meditating, and students playing after school. The proximity between

housing, green spaces, and services reflected the idea of a 15-minute

city—where all basic needs are accessible within a short walk or bike

ride.

One moment that left a lasting impression was watching a

teacher lead her students across a crosswalk. The street was calm and safe—no

honking cars, no aggressive motorcyclists. In Malaysia, school zones are often

chaotic, with jammed roads, impatient drivers, and safety hazards. Here in

Pasir Ris, the system respected the pedestrian, and in turn, the pedestrian

felt safe.

Orchard Road vs. Bukit Bintang: A Tale of Two Cities

In the evening, we visited Orchard Road to draw comparisons with Malaysia’s Bukit Bintang. Both are retail corridors, but the experiences they offer are vastly different. While Bukit Bintang tends to feel cramped and car-centric, Orchard prioritizes the pedestrian.

Orchard Road is a wide boulevard, flanked by well-maintained sidewalks, mature trees, and coordinated building setbacks that allow for public plazas and shaded walkways. There were food carts selling ice cream, musicians busking at intersections, and people resting under trees or enjoying the many open-air seating areas. Despite the presence of high-end malls and global luxury brands, Orchard Road felt accessible to everyone—locals, tourists, the elderly, and even children.

What I admired most was how Singapore allowed “informal urbanism” to flourish within a formal structure. These elements were embraced, and they contributed to the vibrancy of the street.

Key Observations and Takeaways

Reflecting on the day, I came away with three key insights:

- Designing

with Nature: From Changi to Pasir Ris, Singapore doesn’t treat

greenery as an afterthought. Trees, shrubs, and gardens are embedded into

the infrastructure. They cool the environment, soften the urban form, and

contribute to public health.

- People

Before Cars: Whether in residential neighborhoods or commercial zones,

the pedestrian experience takes priority. This means wide sidewalks, safe

crossings, integrated public transport, and traffic calming measures.

- Public Space as Community Engagement: Parks in Singapore aren’t ornamental. They are functional, inclusive, and accessible—supporting everything from exercise and play to social gatherings and food markets.

A Vision for Malaysia

|

| Kuala Lumpur walking city vision (Image Credit: Urbanist Kuala Lumpur) |

As I compared these experiences with my own city of Kuala Lumpur and

other parts of Malaysia, I couldn’t help but wonder: What would it take for us

to reach this level of thoughtfulness in design and planning? It’s not just

about budgets or political will. It’s about vision. A belief that cities should

be built for people, not just for cars or profit.

Singapore proves that dense cities can still be green,

vibrant, and human-centered. It also shows that policies matter—urban planning

here is not reactive, but proactive. Malaysia has the talent and the resources;

what we need is long-term thinking and a focus on implementation.

This first day opened my eyes to what’s possible. I was

inspired, and more importantly, I was challenged. As an aspiring architect, I

want to design spaces that do more than look good. I want to design spaces that

make people’s lives better.

Tomorrow, we dive deeper into the heart of Singapore’s

urban planning—from Chinatown to the city centre. Stay tuned.

[Part 3: A Deep Dive into Urban Layers - Singapore City Centre]

Link: https://vooikenttravel.blogspot.com/2025/06/part-3-deep-dive-into-urban-layers.html

- GRAZIA Malaysia. (2025). Can We Achieve the Goal of Turning KL into a Walkable City? https://www.grazia.my/culture/can-kl-be-a-walkable-city/

- Obel Award, & Moreno, C. (2021). Definition of the 15-minute city: WHAT IS THE 15-MINUTE CITY? https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362839186_Definition_of_the_15-minute_city_WHAT_IS_THE_15-MINUTE_CITY

.jpg)

The jewel changi airport is a must go place !!!

ReplyDelete